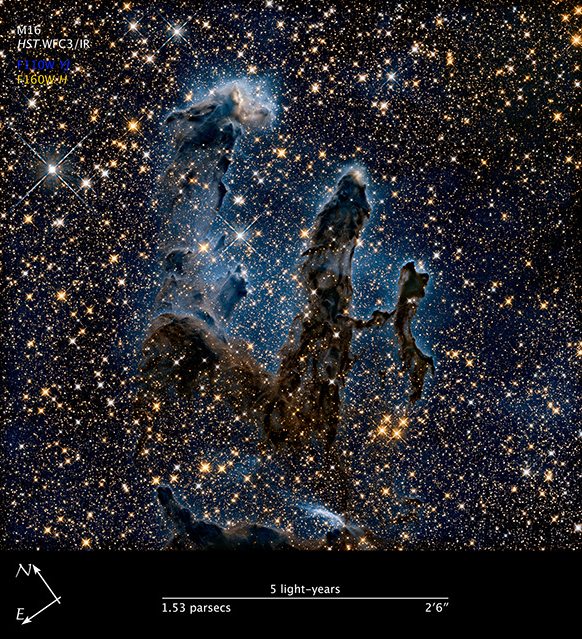

On January 5, 2015, NASA released a high-resolution version of the “Pillars of Creation,” an iconic image originally captured by the Hubble Space Telescope on April 1, 1995. To celebrate its upcoming 25th anniversary in April, Hubble captured the pillars again in a sharper, wider image, and around the globe, people in need of a new desktop background rejoiced.

Here are 8 facts about the Pillars of Creation.

1. The Pillars of Creation are 6,500 light-years away.

Before the Hubble Space Telescope initially photographed the Pillars of Creation in 1995, astronomers had only ever observed them from the ground. An astounding 6,500 light-years away from Earth, the Eagle Nebula (AKA M16), home to the Pillars of Creation, is still close enough to view with the naked eye. If you’re into stargazing, the pillars sit in between the Serpens and Sagittarius constellations in the night sky.

The image above shows the Eagle Nebula with the Pillars of Creation at the center.

2. Over 30 different images went into the original Pillars of Creation.

Did you think this kind of celestial beauty comes easy? Think again! Arizona State University astronomers Jeff Hester and Paul Scowen had to piece together 32 separate images taken by the Hubble’s camera in 1995 in order to achieve the epic final product. Some of them even looked like this.

Why so many pictures? Roughly the size of a baby grand piano, the Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2) aboard the Hubble in 1995 was actually four separate cameras that each captured a different part of the entire object. Each of the four cameras took two images using four different filters.

Today, the Hubble has a new and improved camera that captures even more than the WFPC2.

3. The Pillars of Creation are also a place of destruction.

The pillars themselves, which astronomers also refer to as “elephant trunks,” are basically like little stellar nurseries, made up of hydrogen gas and dust. Inside the pillars, new stars feed off of the gas clouds.

At the same time, a group of massive, young stars (not on camera) is illuminating the entire scene from above, and slowly destroying it. The ultraviolet light from new stars erodes the pillars of dust and gas in a process called photo-erosion.

“The gas is not being passively heated up and gently wafting away into space. The gaseous pillars are actually getting ionized (a process by which electrons are stripped off of atoms) and heated up by radiation from the massive stars. And then they are being eroded by the stars’ strong winds (barrage of charged particles), which are sandblasting away the tops of these pillars,” said Scowen in a press release from NASA.

The whole process is pretty similar to how buttes are formed in the American west. In this case, the denser tops of the pillars are like the hard rock of buttes, able to withstand more erosion and determine the shape of the rest of the formation as lighter material around them is blown away. Strangely enough, while the massive off-camera stars are eroding the pillars, their intense light is also creating enough chaos and pressure in the pillars to create even more new stars.

4. The pillars are really, really big. Like really big.

The pillar on the left is a little over four light-years long, or 40 trillion kilometers! The entire complex is five light-years wide. Our solar system is smaller even than one of the teeny-tiny finger-like protrusions at the tops of the pillars.

To put it all in some sort of perspective, the entire Milky Way galaxy, home to our solar system and the Eagle Nebula, measures about 100,000 light-years across.

5. This could be what it was like when the Sun formed.

Evidence of radioactive shrapnel from a supernova in our developing solar system suggests that our Sun formed alongside a cluster of other massive stars, like the cluster in the Eagle Nebula responsible for the Pillars of Creation.

“That’s the only way the nebula from which the Sun was born could have been exposed to a supernova that quickly, in the short period of time that represents, because supernovae only come from massive stars, and those stars only live a few tens of millions of years,” Scowen told NASA. “What that means is when you look at the environment of the Eagle Nebula or other star-forming regions, you’re looking at exactly the kind of nascent environment that our Sun formed in.”

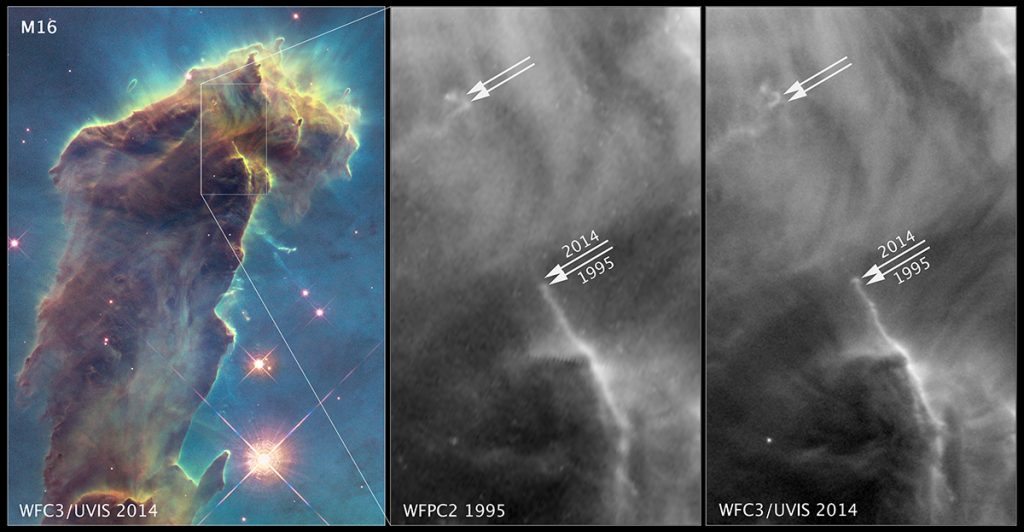

6. It might not look like it, but the Pillars of Creation have changed since 1995.

Scientists have noted that “a narrow jet-like feature” has stretched 60 billion miles at a rate of 450,000 miles per hour between 1995 and 2014. This feature may have come shooting out of a newly formed star, which makes a lot of sense considering that the pillars are basically giant star factories.

7. The Pillars of Creation probably don’t exist anymore. It was only a matter of time until a supernova came along and destroyed them…

I know, you’re looking right at them. But what you’re actually seeing is 7,000 years old.

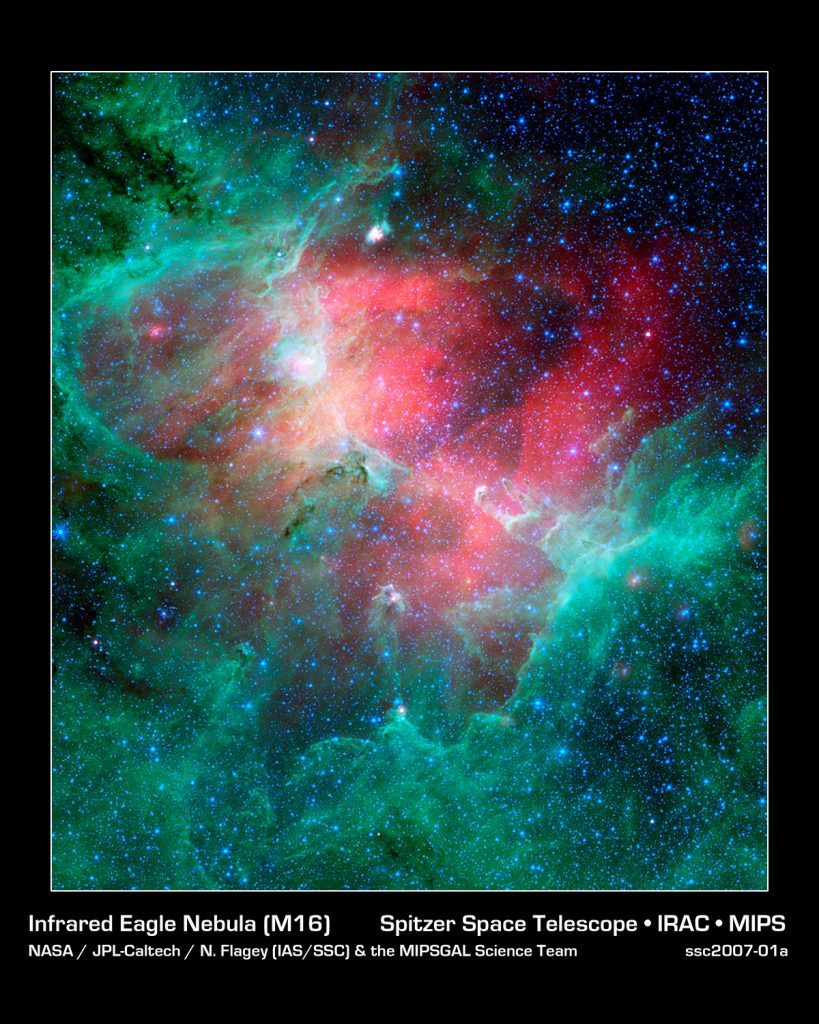

In 1997 NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope captured an image of the pillars next to a giant, hot cloud of dust. Astronomers began to speculate that a massive star exploded, somewhere around the upper-left corner of the image above.

The shock wave from this supernova would have traveled through the Eagle Nebula, heating up dust and toppling things over. You can see the extra-hot dust colored red in the image above.

Astronomers now believe that this supernova probably destroyed the Pillars of Creation… over 6,000 years ago. They’ve predicted that a supernova would destroy the pillars for quite some time, due to the amount of “ripe” stars in the area.

Why can we still see them today? It takes light from the Eagle Nebula about 7,000 years to reach Earth, so we won’t see drastic changes in the pillars for another 1,000 years.

8. The technology behind the new images brings us closer to seeing the first stars and galleries in the universe.

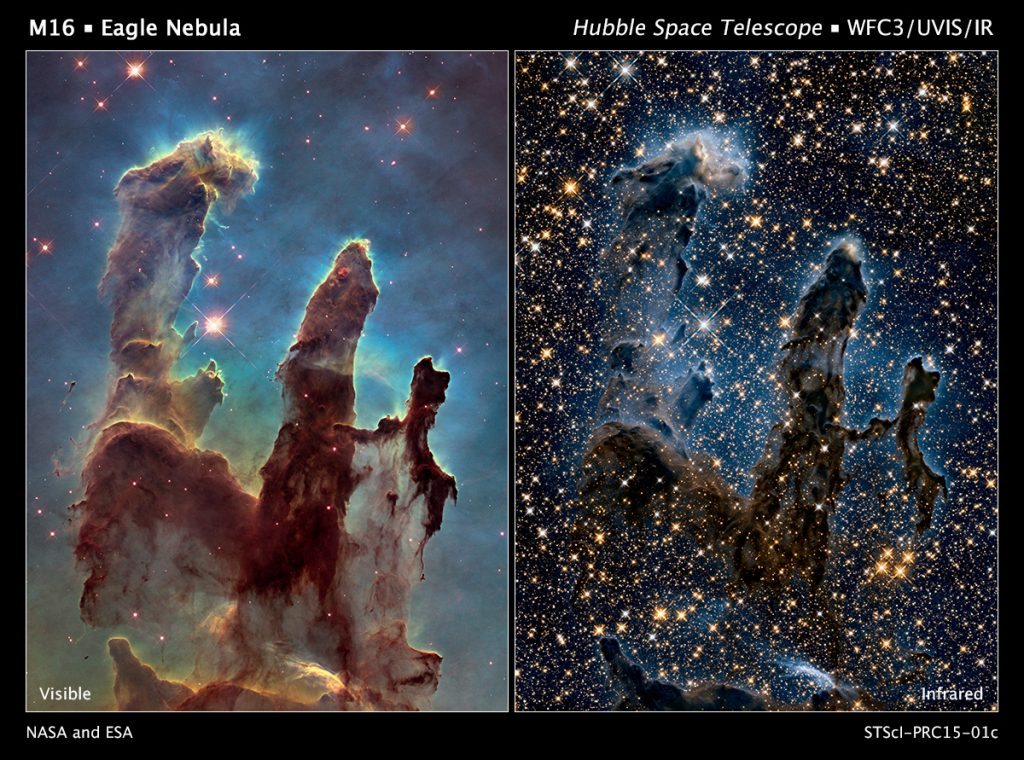

The Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) on board the Hubble is bringing NASA astronomers closer to observing the origins of the universe. This camera, which captured the most recent images of the pillars of creation, can take photos in near-infrared light as well as visible light, bringing NASA astronomers even closer to the James Webb Space Telescope planned to launch in Oct. 2018.

The WFC3 allows us to see interstellar formations in two “channels.” The UV-visible channel is useful for viewing nearby galaxies as well as newly-forming, dynamic galaxies. The near-infrared channel is great for capturing distant galaxies. In the picture above, the near-infrared image shows stars hidden inside and behind the pillars that can’t be seen in visible light.

Using this technology, we can now observe stars and galaxies that are so old and far away that they only give off light in infrared wavelengths, giving us a glimpse into the beginning of the universe.

Comments are closed.